A question that has dogged me from the beginning of my study of shawl “talim” (the instructions in text form that convey design information to the weaver) is how many picks of weaving are made according to each line of the instructions. On my recent trip to Kashmir, I associated other people’s dissatisfaction over the jagged appearance of woven motifs with the prevailing practice of four picks per talim line, and tried to make the key part of my message to shawlweavers my argument for two picks per talim line. It is a technical subject, where analysis of the resolution of the design in the weave structure guides workable routines of the weaver’s practice to produce the best results, typical of the historical standard, from which contemporary practice has slipped.

The traditional Kashmir shawl is woven using a combination of twill weave structure, and tapestry-style selection of different-coloured wefts according to the requirements of the design. The twill structure is one of the simplest, described as a 2/2 straight twill, where each weft thread passes over two warp threads, under two warp threads, and repeat. In the next pick the warp threads that the weft passes over two and under two, shift one thread to the right. After four such steps, the weft thread is again passing over and under the same pairs of warp threads as in the first step. So one “weave unit”, the smallest identical set of threads in the weave structure, involves four warps and four wefts.

In practice, the harness of the weaver’s loom raises two and lowers two out of each four warp threads – each raised pair called a “nal” – creating the “shed” or space that the weft is passed through. (The weaving is done with the back side of the fabric uppermost on the loom, so the front is face down.) Each nal that the weft passes under produces one stitch of weft colour in the design on the front of the fabric. The number of stitches, or nals – or pixels in other words – in the width of the design will be one quarter the number of warp threads. It is extremely difficult, but not impossible, to produce any more detail in the width of the design than the number of nals allows.

The warp threads of the fabric will likely all be the same colour – or possibly arranged in stripes – which will contribute somewhat to the background colour of the design. It is really the placement of the different-coloured wefts that define the design. In each pick the talim prescribes a series of steps in which a weft of one colour passes under a given number of nals, then is exchanged for another weft colour which passes under the next number of nals, and so on, until the pick is complete from one selvedge to the other.

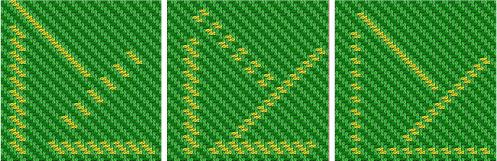

Now the question: for the next pick, is the same – or a new – line of instructions to be followed? There are three reasonable possibilities. In the first case, it would be logical to follow the same line of instructions for four picks, the complete weave unit; that would provide the same design resolution lengthwise as widthwise, and the next set of four stitches comprising a pixel would be directly above the previous set. The design could be mapped on a square grid for shawlweaving just as it is for hand-knotted carpets. Following this logic in its simplest form, the four stitches would line up in one diagonal row as the nals shift by one warp thread in each of the four picks [on the left in the illustration “twill line comparison”]. These little diagonal rows have the most jagged appearance and disruptive effect on the small details of the design. Because of this, a refinement has been developed in which one nal is deducted at the beginning of the third pick, so that the third and fourth stitches appear more directly above the first two, instead of continuing in that diagonal row [at the center in “twill line comparison”]. This tactic tends to balance and reduce the effect of the four-step twill diagonal progression on the design, and is the widely-adopted shawlweaver’s practice today.

Jumping to the third possibility, the weaver could have a different set of instructions for every single pick. I haven’t seen this in written form, but in a large, continuous design the weaver would need a way to keep track of which pick out of the four in each weave unit is being worked on, before resetting the starting point at the beginning of the next weave unit. Memorization plays a big part in weaving repeated motifs, and I can accept that the weaver may have memorized pick-by-pick adjustments to make perfect all the details of small repeated motifs.

In the second possibility, the weaver would follow a line of talim instructions for two picks of weaving, so there would be two lines of instructions for each weave unit. After treadling for the first pick, each weft is inserted in sequence from left to right, as the talim text appears to be written. The next shed is treadled and each weft is inserted from right to left, by reading the same talim line steps in reverse order. Each weft is returned to approximately its starting point at the previous pick, except for the shift of two warp threads caused by the two treadlings. Advantages to this are: it confirms that the counting of the instructions was followed correctly; it facilitates the snug double-interlock of weft threads (that doesn’t need to be discussed here); and it provides a familiar starting point for each weft for the next line of instructions, which will probably be mostly similar to the previous line.

My argument that the second case was the basis for shawlweaving practice during its golden era, is threefold: the evidence for it is there to see in antique shawl fabrics; surviving shawl talims mark the alternate lines of talim text to establish their relationship within each weave unit; and it enables superior resolution, grace, and detail in shawl designs.

On two illustrations of antique shawl fabrics, both from the late 19th century, I’ve noted some examples of stitches appearing in multiples of 2’s and 6’s, not just 4’s as current practice would dictate.

On two illustrations of antique shawl fabrics, both from the late 19th century, I’ve noted some examples of stitches appearing in multiples of 2’s and 6’s, not just 4’s as current practice would dictate.  Though the style of the designs differ, they are both relatively large-scale, beyond the scope of memorization, and so, dependent on recorded instructions. I have seen one claim reported by E. G. Marin in 1933 that the talim system was invented in the 18th century. In another shawl fragment dated to the early 18th century at the latest, a mistake in the design between two identical motifs suggests written instructions were being imperfectly followed, and also shows some details in multiples of 2’s.

Though the style of the designs differ, they are both relatively large-scale, beyond the scope of memorization, and so, dependent on recorded instructions. I have seen one claim reported by E. G. Marin in 1933 that the talim system was invented in the 18th century. In another shawl fragment dated to the early 18th century at the latest, a mistake in the design between two identical motifs suggests written instructions were being imperfectly followed, and also shows some details in multiples of 2’s.

Each line of a page of talim text, whether it covers the full width of a smaller repeated design, or a section of a larger continuous design, spans a consistent number of warp threads – the total number of nals in each line will be the same. But if the instructions in the following line have shifted by two warp threads, those two threads may appear to be unaccounted-for. In the case of the current practice where one nal is subtracted at the start of the third pick, that is only necessary at the selvedge because subsequent repeats or continuations follow the correction automatically. Where the instructions change for each two picks, every alternate line, to account for the orphaned warp threads, will show a “half” nal at the beginning and end of the line of text, which together with one less “complete” nal will add up to the same total number of nals in each line.

This feature can be seen in the illustrations of older shawl talim text – a half nal is written as a straight vertical stroke, or a horizontal tick added to the number symbol it is combined with. Each half nal in this position will typically be the same colour as the next adjoining half nal, and will be woven as one.

This feature can be seen in the illustrations of older shawl talim text – a half nal is written as a straight vertical stroke, or a horizontal tick added to the number symbol it is combined with. Each half nal in this position will typically be the same colour as the next adjoining half nal, and will be woven as one.

This arrangement of rows of nals with half nals at the ends of alternate rows, to represent the off-set of the twill treadlings, can be helpfully visualized as a “brick” grid, where each brick represents one nal and two weft stitches. The height of two bricks (four wefts) would be the same as the width of a brick (four warps), and the corresponding bricks in the next two rows would be positioned directly above. So to create designs on a brick grid of these proportions would be very similar to designing on a square grid (where each square represents four wefts and four warps) but it would provide a closer representation of the diagonal twill weave structure, increased resolution, smaller details, more delicate and responsive curved lines, and other subtle optical illusions familiar to tapestryweavers. To fully explore these possibilities and other refinements such as actually weaving half nals, goes beyond the scope of this article, and requires designing informed by the weaver’s experience of what’s practicable and how it will appear in the finished fabric. Not all of the legacy of shawlweavers’ skills can be captured in a few lines of instructions.

The advent of computer-assisted design has been a big improvement over designing on grid paper, facilitating corrections and alterations, and generating the line-by-line instructions convenient for weavers. In Kashmir, professional-quality software is available for the hand-knotted carpet industry that provides talim-style instructions using the “shawl alphabet”, the same shorthand symbols for numbers and colours developed for shawlweavers, but based on the square grid suitable for carpet where the knots line up in rows and columns. (It was pointed out that in some carpet designs every line of instructions may indeed end in a half unit, but this is only meant to show that, in the case of mirror-repeat designs, the column that the design turns on is not repeated.) That this software is considered adequate for contemporary shawlweavers, encourages the less satisfactory practice of four picks per talim line. Fortunately, from early in my studies I had a CAD program called Stitch Painter, that provided the brick grid used to design for a type of bead weaving, but it only produces line-by-line instructions using cumbersome Western letters and numbers. What’s needed is a program that uses the brick grid and familiar shawl-alphabet characters. Shawlweavers will recognize that it more accurately reflects the progression of threads on their looms, and appropriate design instructions will prompt them to reach finer results.