Got the world on a string

•19/04/2011 • Leave a CommentWhy I Won’t Vote

•19/04/2011 • Leave a CommentIt’s not out of laziness or disinterest, but rather frustration and contempt for the current political process. Churchill’s comment about democracy being better than the rest is faint praise. Gandhi’s parry that western civilization would be an idea worth trying, better describes our shortcomings. My apologies for the intrusion of this issue on a site where I hope to range over positive, constructive contributions. It’s on the occasion of the federal election campaign in Canada, and newsmedia are fixated on the topic to the exclusion of real events. Any comments I receive on this, I’ll reply to them with due consideration, but I won’t post them.

Politicians are all scoundrels. Some few of them, by dint of perennial success and ingratiating familiarity, might eventually be considered loveable scoundrels, but scoundrelship is the prerequisite. Claims of wanting to “serve the people” are a crock – all aspiring politicians already think they know what’s right for the people and are simply looking for their chance to put it across. Politicians arrive on the scene at the peak of their popularity, and do not leave until they have sunk to their lowest.

Why are there no politicians of exceptional character, insight and ideas? Party politics systematically weeds them out. Adherence to the party platform and pronouncements given by the party leader is absolutely required. And because all the parties are competing for the same electorate, they all want to represent, or claim that they represent, the central, majority viewpoint on all issues. Kim Campbell notoriously said that an election campaign was no time to discuss real issues – it’s certainly no time to discover where parties really stand on issues. Can the electoral system be improved? I don’t think proportional representation is the answer, because it puts even more emphasis on party affiliation – aggregate vote totals determine how many party candidates are elected, with even less regard for which candidate in which constituency. Recent experience argues poorly for the ability of parties to work together.

There is no party or candidate with the courage to represent the leftist views I hold. I learned this when I regrettably helped elect the so-called NDP government of Bob Rae in Ontario twenty years ago. One of his government’s moves was to appropriate and debase the meaning of the term “social contract”. Since then, I have not voted provincially or federally, where party politics is played. To vote for “none of the above” is not acceptable to me. My consent to be governed is withheld, and I am not bound by any “social contract” in its original sense. Nevertheless I choose in most circumstances to behave myself, responsibly but not obediently. In the same way that I try to behave well ethically, but not out of fear of God. It is because I am willing to stand by and be judged for my actions, that I am careful what I subscribe to. For example, it is sometimes said that Canada is “at war” in Afghanistan, and now Libya. Excuse me, I am absolutely not “at war”, I do not support either intervention, and I grieve the human toll on all sides. “Western civilization”.

How to weave a Kashmir shawl

•09/03/2011 • 1 Comment

When Ellen and I travelled together to India in 1985-86, she had just graduated from the Ontario College of Art, and I had been weaving tapestries for several years, so both of us were keen to seek out Indian textile craft traditions. We encountered the best example of tapestryweaving in the first days of our trip, in Kashmir. I was left fascinated by the challenge of how to interpret design information given in line-by-line, stitch-by-stitch instructions, into tapestry images woven in a twill fabric, not just plain weave, and not to mention at 80 threads to the inch. It seemed that no Western observer, early or recent, had known enough about weaving to explain. The early ones shrugged it off as “loom embroidery”; more recently we can at least share the evidence of detailed photographs in the many opulent coffee-table books. I began to study the subject in earnest for an OCA course paper in 1990, casting around for descriptive accounts, and making practical experiments springing from my tapestryweaver’s expectations. At the same time, Kashmir’s ongoing struggle for some form of autonomy became more entrenched and dangerous. Given the few fragments of documentary evidence or useful comments, my knowledge of shawlweaving is largely self-taught and reverse-engineered, to discover how to get to the resulting fabric. Popular interest in the historic paisley or Kashmir shawl has provided me many opportunities for published articles and talks.

Weaving has always been inherently digital, but understanding what that means is more recent. The advent of computer-assisted design and a revival of production in Kashmir’s proud tradition today, offer opportunities to improve working methods and recreate designs from antique shawl fabrics. The prospects for the survival of this obviously anachronistic handweaving specialty seem better than when I started. It’s more remarkable to me that such a sophisticated digital understanding of images would form the basis of a thriving weaving industry in Kashmir 300 years ago.

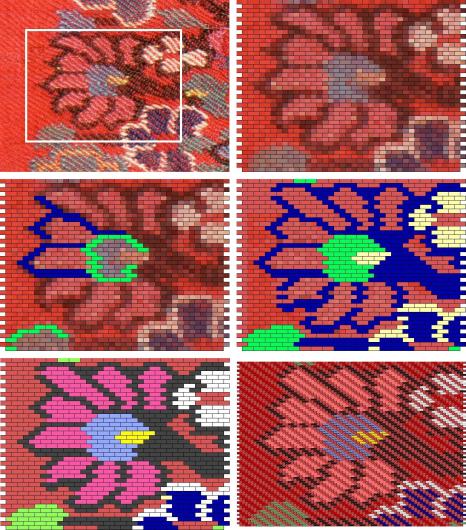

This set of six images was prepared for an article “Decoding the Talim” in the September 2010 issue of Marg magazine. They show my step-by-step method to reconstruct the design instructions from a good photograph of an antique shawl fabric.

The first image, top left, shows my selection from a newly published photo of a shawl fragment (“Pashmina”, Janet Rizvi with Monisha Ahmed, Marg Publications, 2009), chosen for the clarity and charm of its design, and because it is sharp enough to see each thread. In the second image, I copied and pasted my selection onto an appropriate-size brick-grid document in Stitch Painter, a grid-based “paint” program. As the article explains, because the coloured weft threads appear in multiples of two, in a 2/2 twill fabric where the weave unit is 4 by 4 threads, each weave unit is represented by one brick in each of two rows of the brick grid. The next images show stages of hand-correcting the diagram, clarifying the pasted version by close inspection of the photo. Design instructions can be read from the bottom-left image by counting the bricks of each colour in a row and weaving the same numbers of stitches, for two complete rows of threads. The final image shows what this would look like with each thread represented, to compare with the original photo. The instructions, how many stitches (or carpet knots) of each colour in the row, can be written down in a kind of shorthand, and is called the “talim” of that design.

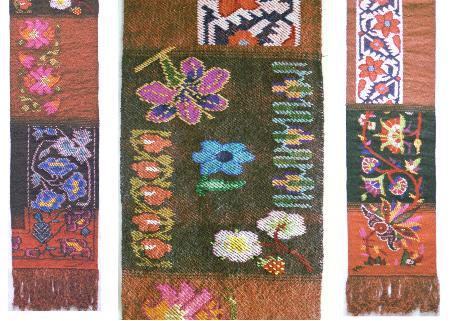

Taking this process to its logical conclusion, I have woven two samplers of my favourite antique shawl motifs, generally from the earliest surviving fragments of the Mughal period. One is a collection of small, free-standing motifs that are repeated in rows in the shawl’s wide end-panels; the other a collection of side-border designs. A portfolio including a text-based talim for each design, is available on CD.

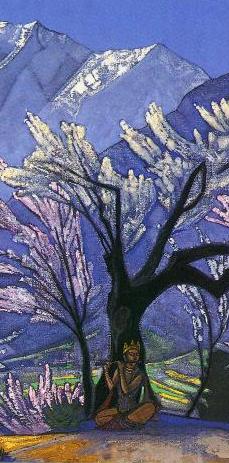

Nicholas Roerich (1874 – 1947)

•05/03/2011 • Leave a CommentA person who has popped up continually in my path over decades is Nicholas Roerich. It’s uncanny. Initially one of my art school teachers, looking at my style and interests, recommended him. I came across a newly-published coffee-table book about him in a bookstore but balked at the price. When my late partner and I toured around India in 1985-86, we found ourselves strolling past the house he retired to in Kulu Valley, and during the same trip spotted newspaper reports about the settling of his son’s estate of the artist’s work. In 1998 I came across the coffee-table book remaindered in a museum gift shop in Montreal, riffled through it, and bought it, realizing only later that it was a French translation. A fascinating history of the “Great Game” in Central Asia called “Tournament of Shadows” (by Karl Meyer and Shareen Brysac) that I happened across, was bookended by accounts of William Moorcroft (a story for another time) and… Nicholas Roerich. I’ve begun to stalk him, to try and spot his ambush before I walk into it. I have a copy of his travel book “Altai Himalaya”. A couple of years ago I determined to pay a lightning visit to New York City to attend a lecture and meet in person someone I’d worked with, part of that other story. Also on my agenda was a tapestry exhibition at the Met, and a visit to the Roerich museum, but fortunately I got talked into trekking up to the Cloisters to see the “Hunt of the Unicorn” tapestries, mistakenly got on the wrong subway train coming back, ran out of time, and missed the Roerich museum – guess it wasn’t meant to be, right then. I don’t know what you know about Roerich, a Theosophist I think, and I’ve left out a lot of background, but… my consistent view is that I don’t wish to have my future foretold, but I would love to know what the heck is going on here.

Under Construction

•28/02/2011 • Leave a CommentAs a blog is supposed to be written in the present tense, I get just one chance to explain how it begins. Longer even than my dedication to tapestryweaving, has been my affinity for South Asia. I first travelled there overland in 1972-73, through many places now more difficult. The photo of me was taken in 1978 by my Nepali host on the front step of a farmhouse, on a hill overlookin g Pokhara on one side, and the Annapurna range on the other. I homed in on one of my photos of the mountains, for my first journey through a woven tapestry wallhanging a few years after. It felt like I had climbed the mountain, stitch by stitch. Years later when I revisited the same vantage point, all the details of the view clicked into place.

g Pokhara on one side, and the Annapurna range on the other. I homed in on one of my photos of the mountains, for my first journey through a woven tapestry wallhanging a few years after. It felt like I had climbed the mountain, stitch by stitch. Years later when I revisited the same vantage point, all the details of the view clicked into place.